Editor’s note: A warning that this story contains disturbing content around sexual assault and suicide.

Oct. 27, 1975 started like any other sunny fall day. The school bell rang at St. Pius X High School on Fisher Avenue and class began. In room 73, students were settling down to read “A Separate Peace,” a book about boarding school friendships being broken apart after war breaks out.

But then came the sound of gunfire next door. Grade 13 student Mike Malone told the Ottawa Citizen at the time he thought it was an explosion in a wing of the school that was under construction. Chaos erupted. Around 30 students jumped out of the windows for safety, with some cutting themselves on the shards of broken glass.

There was no explosion. Robert Poulin, an 18-year-old quiet but academic student, stormed into room 71, pulled a sawed-off shotgun out of his duffel bag, and began shooting at the ceiling. He then stepped out into the hall and took his own life.

Six students in the religion class, including the perpetrator, were wounded. Mark Potvin, 18, Barclay Holbrook, 18, Terry Vanden Handenberg, 18, Kurniadi Benggawen, 18, and Michael Monette, 17, spent a few days in hospital but were later released. But 18-year-old Mark Hough died after undergoing brain surgery.

But that was not the only horror to unfold. Just as Poulin arrived by bike at his Catholic high school, firemen were responding to a blaze in his parents’ basement on Warrington Drive in Old Ottawa South. Once the fire was extinguished, they found the body of 17-year-old Kim Rabot wearing nothing but a jacket and shackled to the bedpost. She was raped and stabbed to death before Poulin tried to burn the evidence.

Five decades is a lot of time to pass. Memories fade and life goes on. But for those who were there that day, the wounds still run deep 50 years later.

Many say it's time for that to change. A bench for the athletic teen who never made it to his 19th birthday has been erected along the Rideau Canal. And on Sunday, a special mass was held at St. Maurice Church on Meadowlands Drive.

The scars of Oct. 27, 1975 are still too much to bear for some, but for others talking about what happened is healing. This is the story recounted by those who were there and their efforts to ensure that what happened during Canada’s second-ever school shooting are not forgotten.

The pandemonium

When the 1975-76 school year began, St. Pius was in the midst of an expansion project. Its student population was rising, and more buildings had to be constructed to create enough classroom and amenity space. But work was delayed, meaning grades 9 and 10 went to class in the mornings with grade 11 to 13 students attending afternoon classes.

Liam Maguire had a spare period that afternoon. He was sitting in the cafeteria located a 30-second walk from room 71, waiting for the bell to ring. All seemed fine until he and about a half dozen others noticed a swarm of students running away from the school.

“What could be going on?” they asked themselves. If it were a fight, teenagers would typically run toward the action, Maguire thought.

“Within seconds, our student body president Mark Arsenault, who was in grade 13 and in the classroom when the shooting occurred, came through the double doors from the hallway and said a shooting occurred," Maguire recounted to the Ottawa Lookout. “The cafeteria went dead silent for what seemed like eternity but was probably just seconds when sheer bedlam broke out. Our thought was whoever did this could still be on campus with a weapon.”

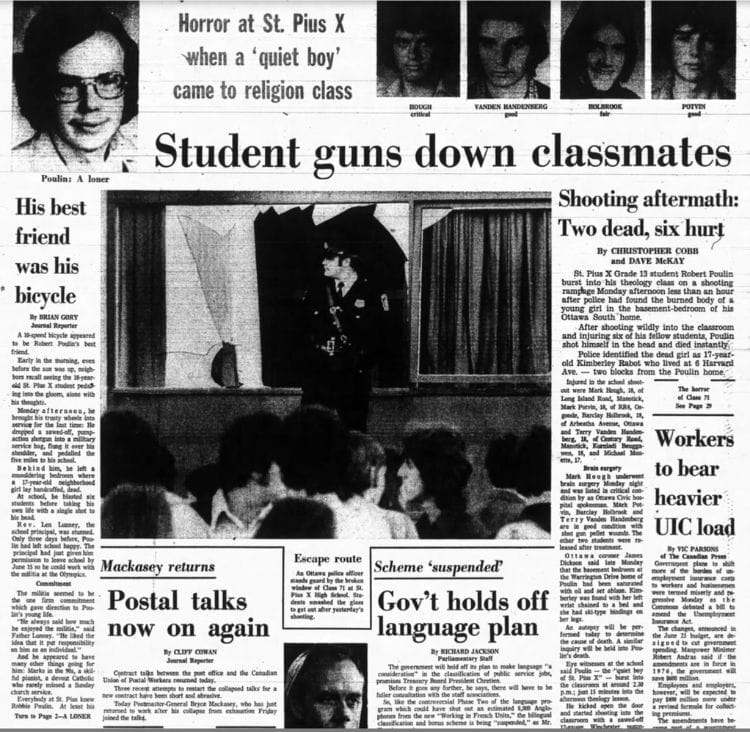

An Ottawa Citizen article from the day after the shooting.

Maguire and his friends ran away from campus and towards Jack’s Convenience, which was located near Meadowlands and Fisher. He used a payphone to call his father and then went back towards the school when police arrived.

Maguire knew Hough – pronounced “Huff” – and rode the school bus with him in Manotick. Hough, who was two grades older, would regularly sit beside him and ask, “how is hockey going?”

“He was a really solid junior player who was playing for the Gloucester Rangers at the time. I was just a tiny little ant compared to him,” Maguire recalled. “He was a really good guy.”

Father Bob Bedard, who was teaching the religion class that day, told the Ottawa Citizen in the 90s that he visited Hough in hospital a few times and prayed with him days before the teen succumbed to his injuries.

“I said a little prayer for him and said he was to be at peace and turn things over to God,” recounted Bedard. “All the while, he was squeezing my hand. Two days after that, he died.”

Moving forward

The community was not given much time to grieve the tragedy before it appeared to be business as usual. Students were expected in class the next day. Grief counsellors were on site, but mental health was managed differently then than it is today. Students were told it was okay to talk about it, but also to move on and forget it happened.

Pat Jennings was in his third year of teaching at Pius in October 1975. He taught morning classes that day and had already cycled back to his Riverside Park home, unaware of what was happening a few kilometres away. He would ride his bike back in a few hours to coach football practice.

A neighbour came over to tell him about the shooting. Jennings stayed glued to the radio until the next day, when he was ordered back to work in the classroom where bloodshed had occurred less than 24 hours prior.

The building on the St. Pius campus where the shooting occurred. The inside has since been remodeled. Photo by Charlie Senack.

Jennings said he can still recall the smell of fresh paint and disinfectant that greeted him that morning.

“Half of the school was still private, and some students worked on the maintenance staff to pay for their tuition. They were part of the ones who had to clean it all up,” Jennings recalled to the Lookout.

“The glass had been repaired, but there were still signs. There were chips out of the wall where the shotgun had gone off, and a lot of the pellet shots were in the ceilings and walls. In class 71, it could have been much worse,” he added.

Jennings recalled being called to a staff meeting that morning hosted by Father Leonard Lunney, who was also the school’s principal.

“He said, ‘you are probably wondering why I called you back on the first day, but I couldn’t imagine you being left alone on your own to deal with this terrible situation’,” said Jennings. “He said it was better for us to be there for one another and to join in faith. There was a binding of the Pius spirit.”

Rabot’s kindness remembered

In her final days, Rabot was on her way to school when Poulin approached her at a bus stop on Bank Street near Trinity Church and said he had something to show her. A studious teenager, Rabot was reluctant, not wanting to be late for class. She was convinced when Poulin offered to drive her.

Rabot knew her neighbour; he lived two blocks away, and she had been at his house for dinner and to play the board game Risk a few times.

That was the last time she was seen alive.

Rabot was born in London, England, but had roots in Sri Lanka (still known as Ceylon at the time). The Rabot family moved to Canada in 1967 as diplomats and began building a life here. Rabot was an avid swimmer, liked houseplants, and had aspirations of becoming a doctor.

Trina Costantini-Powell remembers Rabot for her bubbly personality and big smile.

“Kim had her locker next to mine on the third floor at Glebe [Collegiate]?. She was a year behind me but was a very bright individual and was taking some grade 13 classes,” Costantini-Powell told the Lookout, “I got chatting with her between periods and she had a sister in my grade level. She was going out with a fellow in my homeroom,.”

Costantini-Powell was in her first year at Carleton University when she heard about a shooting at St. Pius and the body found in the Poulin Household. She became even more shocked the next day when she learned the victim was her former classmate.

A few years ago, Costantini-Powell was on a committee helping to organize the 100th anniversary celebrations for Glebe Collegiate. While in the archive room with a handful of others, she pulled back a curtain and found a painting of Rabot. It was displayed prominently in the 1970s room during the reunion.

The painting of Kim Rabot that was recently unearthed in the Glebe archive room.

The CBC learned the painting was commissioned by a friend and classmate, Fred May. Three copies were made: one for him, another for Rabot’s boyfriend, and the third for her sister Sabina Lall. An Ottawa Community Foundation has also been set up in Rabot’s name, with 29 recipients being rewarded in her memory.

Three days after her death, Rabot was buried at Beechwood Cemetery in a light blue casket. Her funeral was attended by a few hundred, including the Poulin family.

While talking to her family about doing media interviews surrounding Rabot’s death, Costantini-Powell’s brother recounted he was in class with Rabot’s younger brother John when they saw what looked like a house fire in the distance.

John, who later testified he was the last to see his sister alive, died in 1994 when the past two decades became too much to bear. Their mother died a few years after Kim.

The inquest

Unlike today, when inquests into horrible events can take years to be heard, it was only a few months before more details came to light about the horrors that happened at St. Pius High School and in a normally quiet Old Ottawa South community.

It turns out that Poulin, who had joined the Cameron Highlanders and was interested in the militia, one day wanted to do officer training. He asked Principal Father Lunney the previous Friday if he could leave the school year early to work security at the upcoming Montreal Summer Olympics. He was told that it wouldn’t be a problem.

But he took a different path when he purchased a 12-gauge, single-barrel shotgun at a George Street Giant Tiger a few days prior. Around the same time, he placed an ad in the Ottawa Citizen looking for a companion.

An Ottawa Citizen article from the Robert Poulin inquest.

The day before the shooting, Poulin played a game of cards with his family. They said he quit early and went to his room downstairs.

Unbeknownst to his parents, who let Poulin live a private life in their basement since his early teens, he had a private P.O. box paid for by his paper route, where Playboy magazines were sent. Police later found 250 pornographic magazines and books, a large collection of women’s undergarments, and a diary which had the names of girls who lived in the area. Rabot’s name was underlined.

Excerpts of the diary were read aloud during the inquest. In it, Poulin wrote about suicide and thoughts of killing his family, but later wrote that he thought death “was the true bliss.”

Poulin wrote that he had a fear of women but didn't want to die a virgin. He even purchased an “everything doll”, but it did not live up to his expectations.

Father Bedard later told the Ottawa Citizen that while “it may sound medieval or superstitious, I have wondered over the years whether evil spirits had interfered.”

Those thoughts came after he spoke with a police officer who saw Poulin’s room and recounted “he had never seen anything so bad.”

The inquest ended after a five-person jury deliberated for six hours. While not in support of a full ban on firearms, they requested that all handguns be banned and that other firearms be sold to people who had only valid reasons for ownership. The jury also requested a full ban on pornography, which would include any kind of material where genitalia was shown.

Gun control came in 1977 under the Pierre Trudeau-led Liberal government, and firearms were divided into three categories: unrestricted, restricted, and forbidden. The same rules apply today.

A time of remembrance

On Sunday, the hall in St. Maurice Church was silent as around 200 family, friends, and former faculty from Pius gathered to remember Hough whose life was taken far too soon 50 years ago.

The 120-minute service was led by Father Roger Vandenakker, a Pius alumnus himself, who was in Grade 9 when the shooting occurred. He spoke at length about how priests still lived at the school in those days, and how people turned to their faith to deal with hardships — including the school shooting.

“We probably had one of the lousiest facilities in the whole city with old buildings and portables. There were lots of new high school buildings all around. But it did not matter, because the buildings were not what made our community,” said Vandenakker. “But part of remembering is there are good memories and tragic memories. There is pain and there is suffering. But it is important not to forget.”

A memorial was set up in memory of Mark Hough at St. Maurice Church on Oct. 26, 2025. Photo by Charlie Senack.

In the decades since a school shooting rocked Ottawa, Vandenakker said similar tragedies have all too sadly become commonplace. The École Polytechnique massacre. In the United States, Columbine. Virginia Tech. Sandy Hook. The list goes on.

But in their tragedy has come an understanding of the need to grieve, to remember, to heal.

“It is important for us to commemorate the tragedy of what happened 50 years ago. And to acknowledge that there was much suffering. Suffering that, at the time, perhaps there was not enough ability or awareness in our society,” said Vandenakker. “Today, there is a much deeper understanding in society and culture on the effects of these events on people's lives and the trauma that affects people in very different ways.”

At a reunion for the graduating class of ‘76, 20 years later, there was no mention of Rabot or Hough, and while alumni took a tour of the school, they passed room 71 in silence. The doors were locked.

But some have visited since. On Facebook, Dennis Curley, who was in the classroom when the shooting occurred, said he faced his fears on the 40th anniversary of the incident and stepped back into the room that had brought a lifetime of trauma.

“For me, it was a very emotional moment,” he said, noting that when he opened the door to leave, memories of seeing Poulin’s body lying there came rushing back.

“That was the image that tormented me with anxiety and nightmares all those years afterwards. Something happened when I went back… since that day I have had no nightmares, no anxiety,” said Curley.

Costantini-Powell said the events that unfolded on that autumn day in 1975 also changed Ottawa in many ways. The innocence a sleepy government town had as a comfort blanket was stripped away from it, she said.

“The shock and fear woke the city up,” she said. “But it also made society change. If you look at it from today's perspective, you can no longer walk into a department store and purchase a gun.”

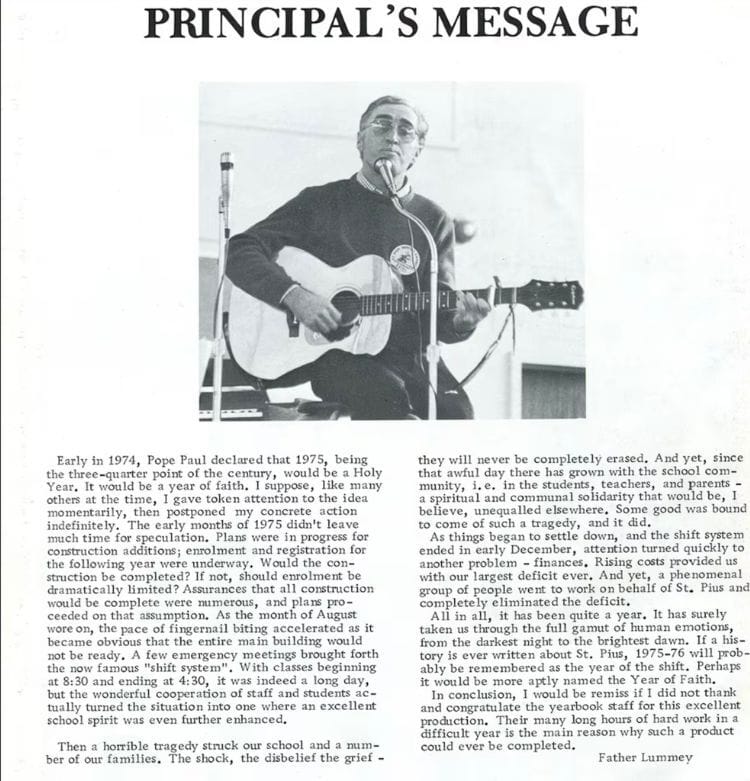

The principal’s message in the 1975-76 St. Pius High School yearbook.

Maguire has never fully left his high school days. Now a historian and owner of a pub that bears his name in the city’s east end, he still goes back to the school every spring and talks to the graduating class about a bursary his graduating class set up to help future students.

“There is not a single time I go back that I don't reflect back to October 27. I always speak in the school cafeteria, and while it's a different one than when I was there, it brings me back to being in the cafeteria that day when the school changed forever,” he said. “I think my former classmates and I are all still so close because of the shared experience we had.”

Today, at St. Pius or anywhere else in Ottawa, there is no official memorial to the lives lost. The Hough family donated a picture of their son to the school, but it has never been hung on display.

Jennings retired from teaching and left St. Pius about a decade after the shooting to work in administration. He hopes a renewed interest in what happened in room 71 will allow for a memorial or plaque to be erected at the school.

“The Brampton shooting was just before St. Pius and they have a beautiful memorial there in the school yard,” said Jennings. “We can't just bury our heads in the sand and pretend it never happened.”