For years, Neil Saravanamuttoo has been a persistent outside voice in Ottawa’s civic debates— from questioning major spending decisions and dissecting city budgets to publicly challenging city hall on issues ranging from transit to Lansdowne. Now, he thinks his time could be better spent fixing issues from inside council chambers.

The finance expert is planning a run for mayor, but there is a catch: he will only do so if residents are willing to organize a “grassroots movement” around him first.

Rather than launching a traditional campaign, Saravanamuttoo says he is testing whether there is enough appetite for change by asking 1,000 people to publicly commit to participating in his municipal election campaign.

“I put out an invitation to find a thousand people — a thousand committed individuals — that feel the way I do: that Ottawa is a city we love, but we’re not getting from City Hall what we expect, and we’re prepared to do something about it,” he said in an interview with the Ottawa Lookout from his home in the Glebe.

Saravanamuttoo argues that a campaign rooted in collective action — rather than personality — is the only way to overcome voter cynicism and fragmentation.

“I actually believe that a thousand committed individuals can win the next election. We can achieve the change that we want in the city.”

While nominations don’t open until May, and voters don’t head to the polls until late October, the race is picking up steam sooner than anticipated.

Incumbent Mayor Mark Sutcliffe has stated he intends to run for a second term. Kitchissippi Ward Coun. Jeff Leiper announced last summer he was eyeing the job after becoming discontented with public transit. Then, a few weeks ago, home builder Alex Lawson announced his name would also be on the mayoral ballot.

For anyone who takes an interest in municipal affairs, Saravanamuttoo is a household name. He spent nearly two decades at Canada’s federal Department of Finance and later served as chief economist at the G20-backed Global Infrastructure Hub.

More recently, he’s the man behind the non-profit CitySHAPES and its Better Ottawa town hall events and podcasts, which he co-hosts with longtime municipal affairs journalists Joanne Chianello and Jon Willing.

Saravanamuttoo grew up in the west end near Carlingwood, attended Nepean High School, and remembers when he could take the Route 65 bus directly downtown. It was a different time, he said, when people could afford to buy a house without parental support, and homelessness “was barely a thing.”

Quoting Prime Minister Mark Carney, Saravanamuttoo said “nostalgia is not a strategy,” but added there is recognition the “city has been, unfortunately, on a downward trend for many years.”

Hong Kong-inspired transit

Saravanamuttoo said OC Transpo users have lost confidence in the system and in city hall’s ability to fix it. He said the first step is “truth in transit,” which would bring more transparency to the issues and validate riders’ concerns.

“We’re spending so much money and getting so little results for it, and we need to be crystal clear about that because we can’t solve the problem until we accept that there is one,” he said. “We need to understand why the system is not working, where the money is going, and how decisions are being made.”

Saravanamuttoo said he could see a citizens’ assembly being established to better understand what transit riders want. He also wants to see projects in the Transportation Master Plan fast-tracked, such as the Baseline and Carling bus rapid transit networks.

But in order to achieve this, Saravanamuttoo said the way transit is paid for needs to change and stop operating on a cost-recovery basis.

“There is no transit system in the world that does that. We need new sources of funding. One I am surprised the city has not adopted already is the idea of a transit development agency,” said Saravanamuttoo. “We are seeing this in Vancouver, and they realize that as they build new transit lines, the value of land around those stations goes up — including the actual transit station itself.”

When the light rail station was built at Tunney’s Pasture, Saravanamuttoo said the city lost out on an opportunity to build towers on top of it.

“That was a terrible mistake. We could have sold air rights to it, we could have put in commercial properties that we could get ongoing revenues from. We can then use those revenues to help fund transit,” he said.

A similar model is also implemented in Hong Kong. There, the MTR Corporation, which operates the region’s subway and rail network, partners with private developers to build residential towers, office buildings, and shopping malls. The revenue it generates accounts for between 40 and 60 per cent of its budget.

The Lansdowne debate

As the city was debating whether or not to move forward with the highly controversial Lansdowne 2.0 file, Saravanamuttoo remained fiercely against the project. During his finance career, the economist said he has seen how other jurisdictions deliver expensive and large infrastructure projects.

Saravanamuttoo said his opinion is that the $418.8 million project is a “terrible use of public money.”

“There are many other priorities across the city we should be spending money on,” he said. “I would much rather take out debt and say each ward could have about $20 million to fund the projects that are a priority for them, rather than pour more money into Lansdowne 1.0, which is actually pretty good.”

Saravanamuttoo admits the city did not get Lansdowne 1.0 fully right over a decade ago but said it is an attractive space.

If elected mayor, Saravanamuttoo said he’s unsure if the current contract could be cancelled, since many details of the agreement are private, but said at a minimum he would want to see how the publicly owned parts of the land could be improved.

“If you look at the east end of Lansdowne, we have public art, a play structure, the skatepark, what will be left of the great lawn, and the orchard. One question we should ask is whether the city is doing enough to manage this,” said Saravanamuttoo.

He suggested creating a non-profit conservancy to manage the space.

“The number one example of this is Central Park in New York City,” the mayoral hopeful said. “Are we using this site to its full potential? I don’t think we are.”

The concern over vote splitting

If Saravanamuttoo chooses to run, he will be among at least two left-leaning candidates on the ballot. Many of his ideas — especially on transit — are similar to Leiper’s. That has some progressives worried the vote could split, giving an advantage to the incumbent, Sutcliffe.

Saravanamuttoo does not see it that way.

In fact, the “programmatic progressive” who served as an economic adviser to Catherine McKenney during their mayoral bid in 2022, seems to think it will come down to a two-person race — similar to what happened three years ago.

In that race, which had an open seat after Jim Watson decided not to seek re-election, there were three main candidates: Sutcliffe, who had a background in business and media; Somerset Coun. Catherine McKenney, who was the left-leaning candidate; and former mayor Bob Chiarelli, who also had stints in provincial politics.

“People worried that Bob Chiarelli was a potential spoiler candidate, and he started very strongly in the polls. He was running somewhere around 15 per cent, but as we got closer to the finish line, people realized that a vote for him presented a risk to their preferred candidate.”

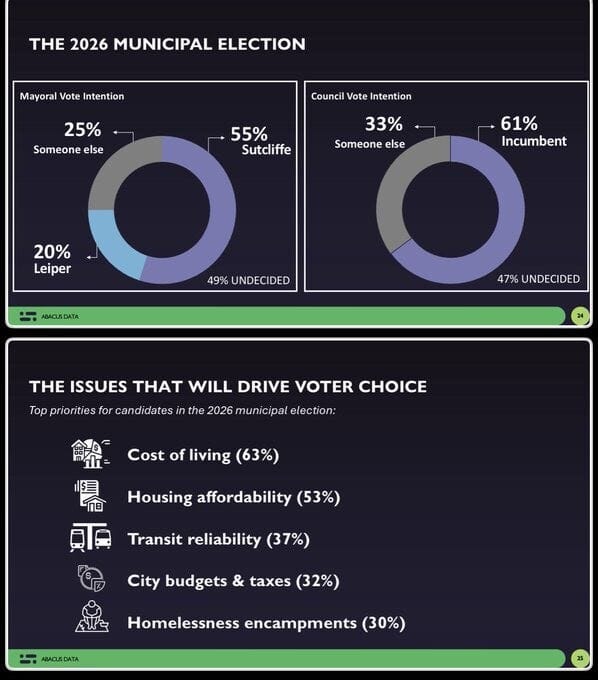

David Coletto shared this snapshot on X of an Abacus Data poll which showed how people are planning to vote for mayor in the municipal election.

Chiarelli took five per cent of the vote, with McKenney coming in second place with 37.8 per cent. Sutcliffe won with a slight majority of 51.3 per cent.

In a race with four well-known candidates, such a high percentage may not be needed to win. Vote splits could benefit any of the candidates, who might only need about 30 per cent if they all receive a similar vote share.

Historically, Ottawa has not voted for more left-leaning mayors. The last was NDP-aligned mayor Marian Dewar, first elected in 1978 and serving until 1985. The registered nurse by trade was perhaps best known for leading Project 4000, in which Ottawa residents helped sponsor 4,000 Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian refugees.

More recently, it is the urban core that votes for left-leaning mayoral candidates. In 2022, McKenney took the greatest vote share in five of the city’s 24 municipal wards: Kitchissippi, Somerset, Capital, Rideau-Vanier, and Rideau-Rockcliffe. They also came close in River, Bay, and Alta Vista wards. The suburban and rural horseshoe surrounding the city has historically voted for more centrist or right-leaning candidates.

A recent Abacus Data poll presented for the Ottawa Real Estate Board showed 49 per cent of Ottawa voters remained undecided about who they wanted to be mayor. Of the 51 per cent who were decided, 55 per cent said they supported Sutcliffe, 20 per cent planned to vote for Leiper, and 25 per cent said their preference was someone else.

Saravanamuttoo said he is taking this as a sign that people are looking for change.

“People really care about this city, and it’s important that we listen to what they have to say — what their priorities are — before we come up with any platform,” he said.

Editor’s note: In Friday’s newsletter we will introduce you to Alex Lawson, who also announced his mayoral run last week, and the heavy hitters who are backing him.